Potentials of life-prolonging effects of probiotics as observed in C. elegans experiments

2022-03-25 11:48

Healthy aging has been a hot topic lately. We’re seeing an increasing number of publications sprouting across the fields of biology and biomedicine and figures like Dr. David Sinclar are gaining voice and attention in the public. Obviously, it’s been a dream since day one for humanity to live not just longer but also in a healthier fashion, and finally, it’s becoming a topic more realistic and pragmatic these days. However, and as always for research in biology, things are complicated, and the only way to gain further ground is to break it down. The scholars of this paper chose to look at the potential anti-aging properties of probiotics, or Lactobacillus fermentum BGHV110 (BGHV110) in a more precise manner for this blog. It’s a human commensal bacteria that are part of our gut microbiota and the link between the functions of such bacteria and autophagy demonstrated in previous publications has caught the eyes of this group of researchers, and they went on, in this paper, to further support the finding by their peers with fresh evidence from the trials done using C. elegans as the model organism.

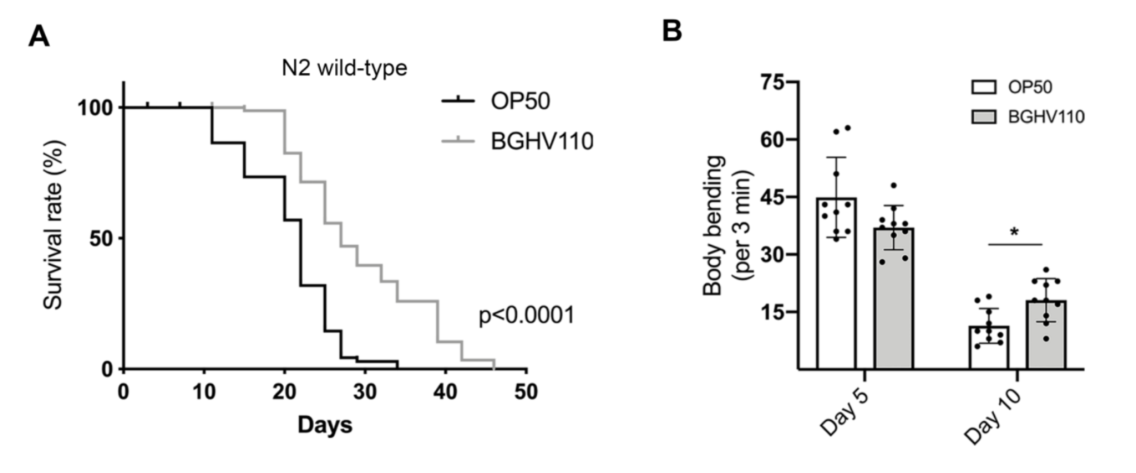

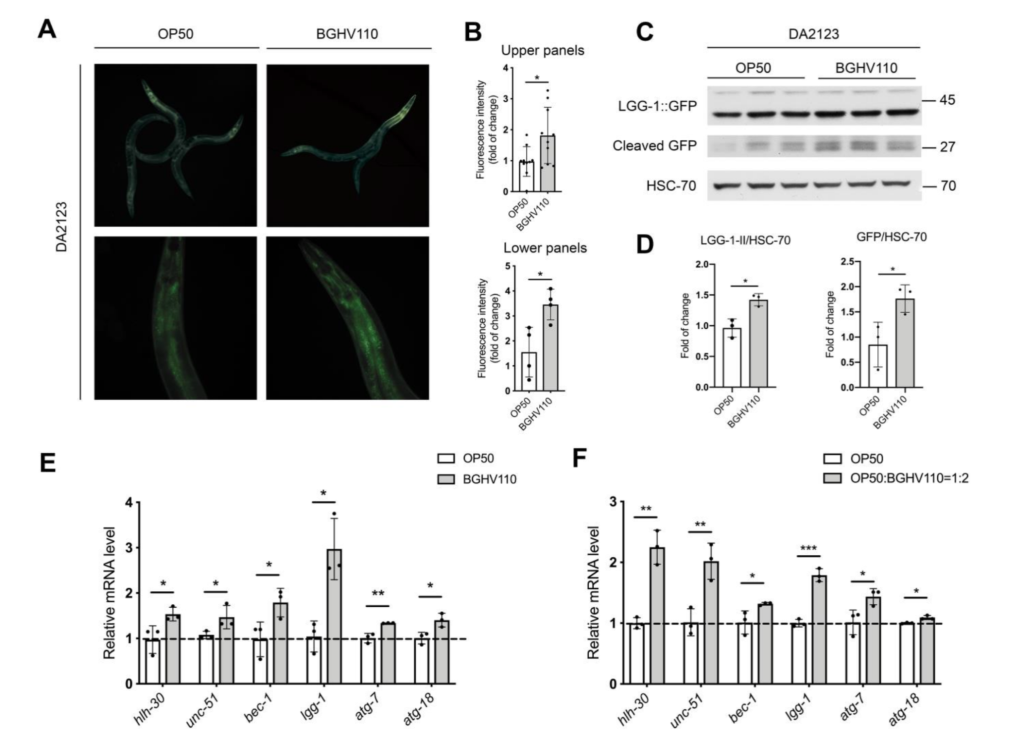

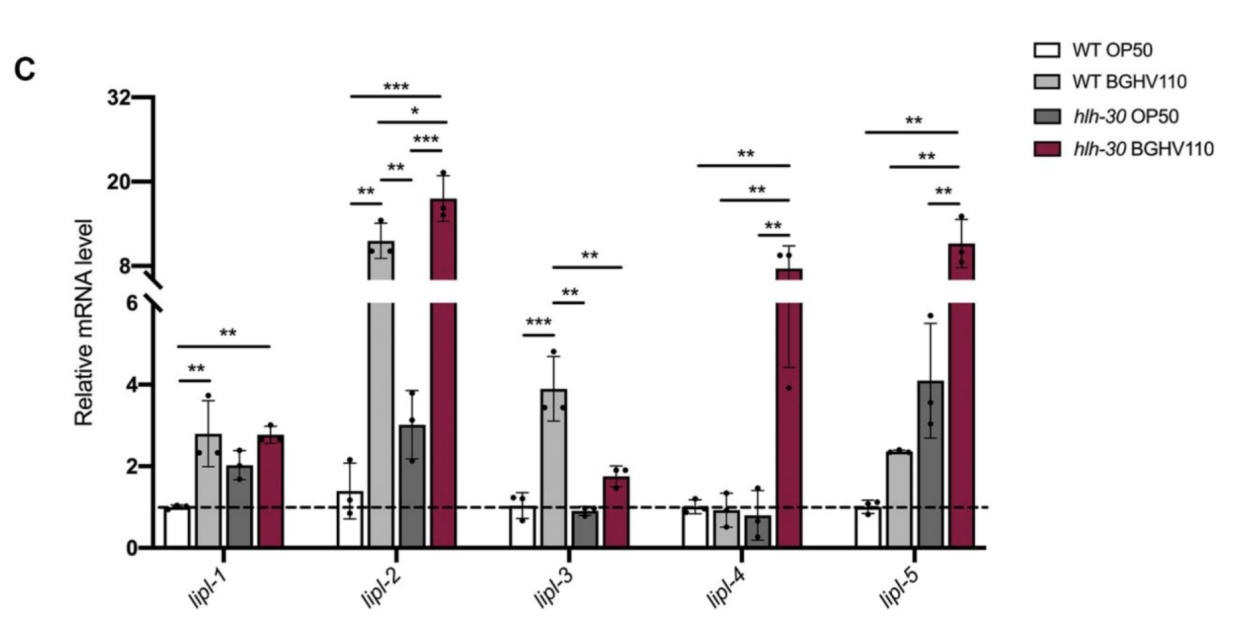

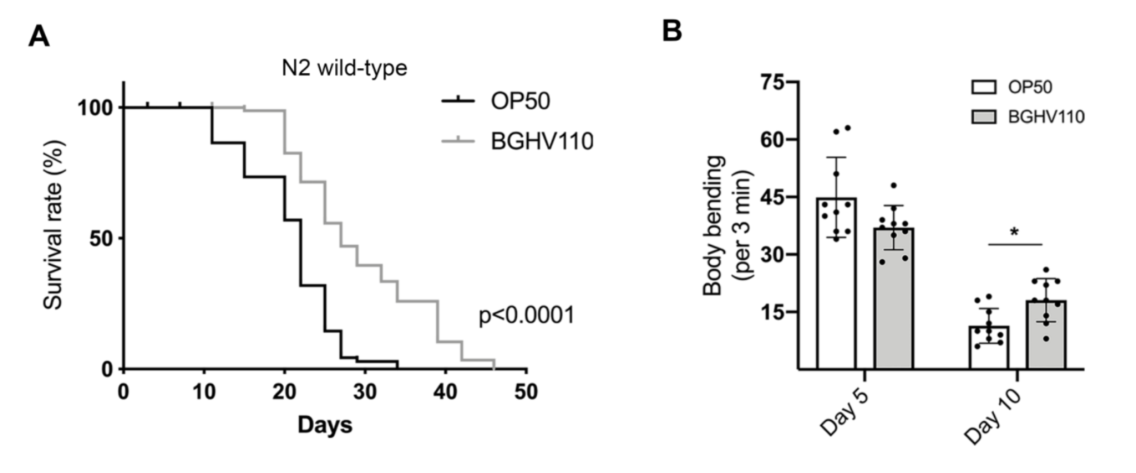

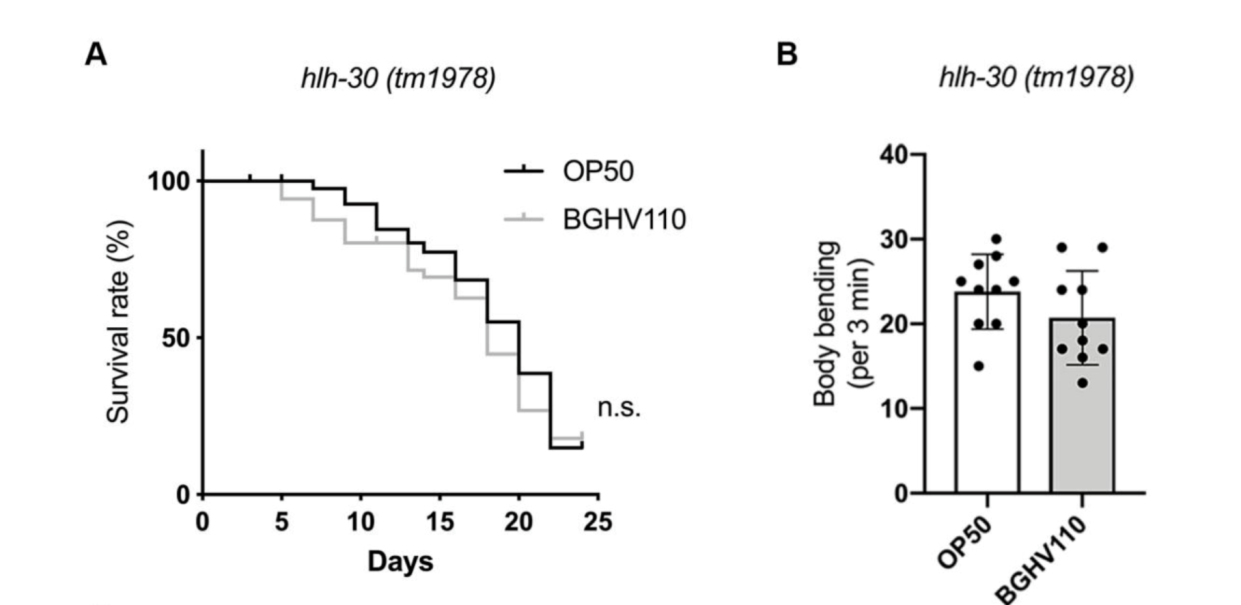

The cornerstone of the results of this paper is that C. elegans fed with the Lb. fermentum BGHV110 bacteria were observed to have a longer lifespan compared to that of the control feeding on OP50, the “conventional” food for lab C. elegans. Interestingly, instead of using live bacterial culture, the researchers recruited in this paper bacteria cells that have been heat-inactivated, or in the form of “postbiotics”. It’s thought to retain to some degree the potential benefits observed in trials with live bacteria, but only safer as they don’t trigger as much immune response from their hosts. The general aging conditions of the worms(the percentage of worms living to certain days), as well as some other fitness parameters such as the body bending rate, were documented for the illustration(Figure 1.). The worms fed with BGHV110 postbiotics were seen to live longer and with better-performing bodies(more frequent body bending in older worms). The possible effects of dietary restriction were ruled out by the researchers since they found that the two groups of nematodes were having roughly the same food uptakes. Then, how about the underlying mechanism(we know that people love to ask “how”s)? The direction being probed here is that all might have something to do with autophagy and an autophagy regulator called helix-loop-helix 30 (HLH-30). To test their hypothesis, the researchers recruited a transgenic strain of C. elegans(DA2123) that are capable of expressing a GFP-tagged version of LGG-1 under the lgg-1 promoter, an orthologue of the mammalian LC3 autophagy marker. By measuring the intensity of the fluorescence, the researchers would then be able to determine the degree of autophagy going on inside each nematode. The results were promising. The intensity of the GFP fluorescence, quantified, as well as the transcript level of genes(e.g. unc-51, bec-1, lgg-1, atg-7) encoding proteins involved in different steps of the autophagy process were found to be much higher than that of the control(Figure 2.), meaning an upregulated bio-performance by the feeding of BGHV110. What’s more, the same properties were also observed for the worms “supplemented” with BGHV110(they were feeding on a diet of OP50 and BGHV110 in a 1:2 ratio).

Figure 1. Conditions on aging and body-bending between worms feeding on BGHV110 and OP50.

Figure 2. Analysis on autophagy.

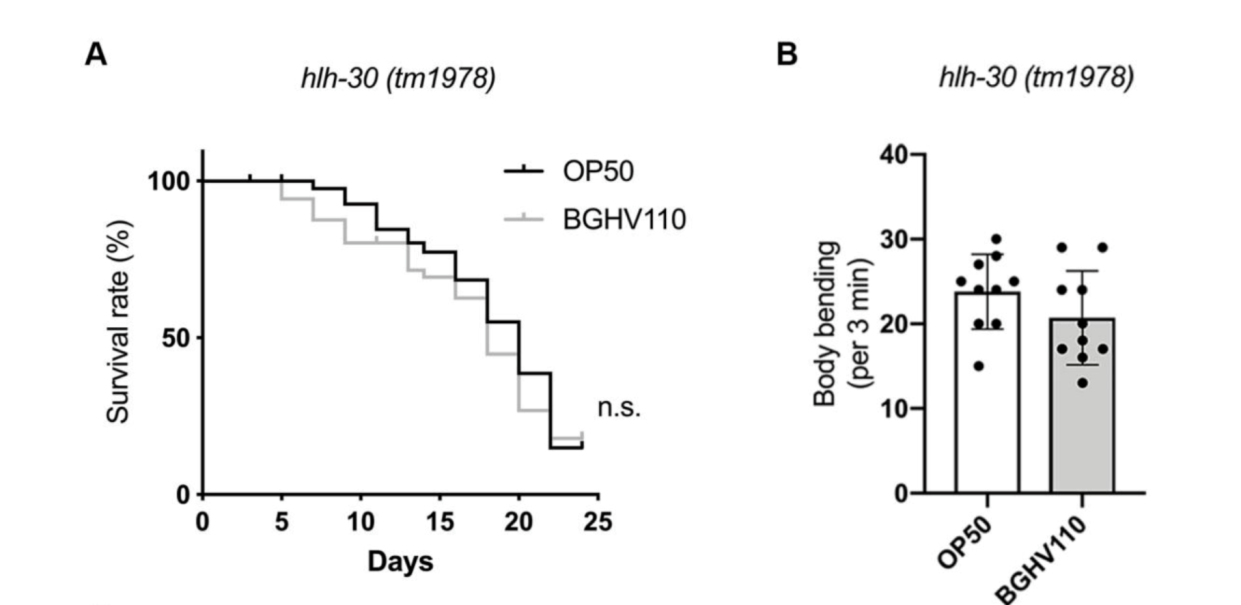

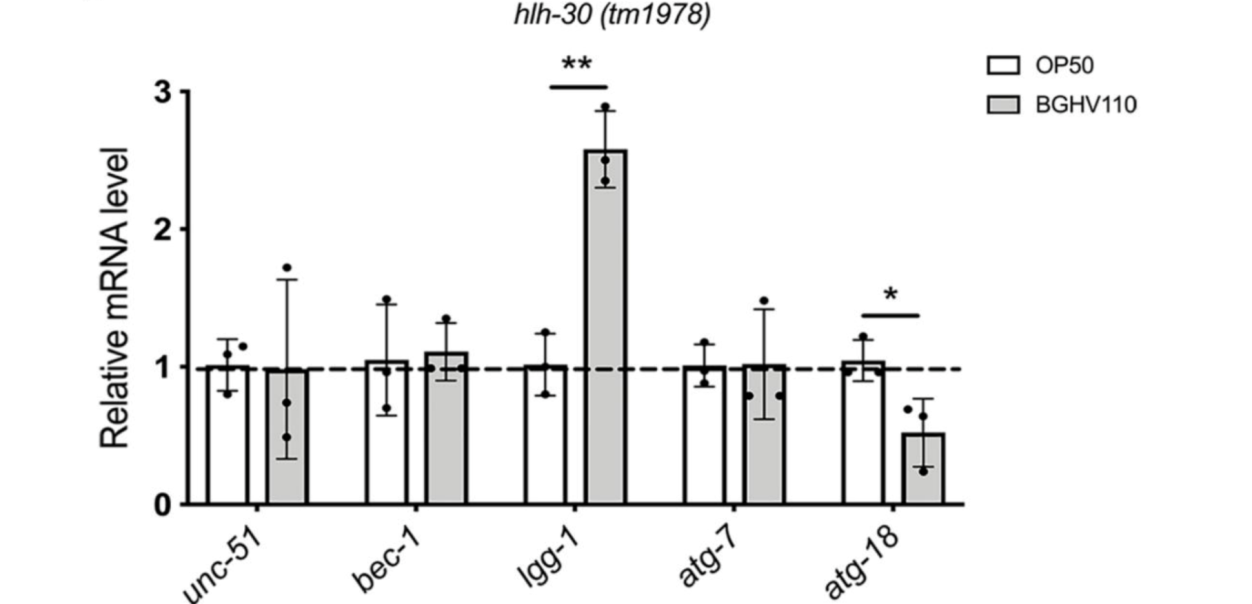

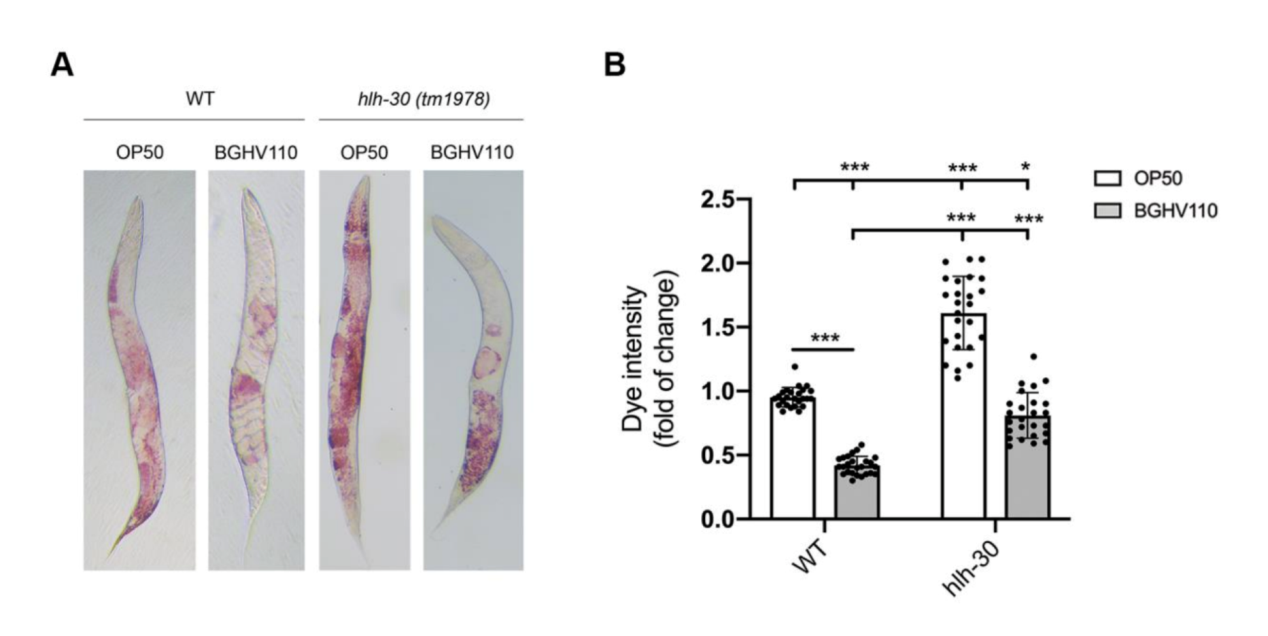

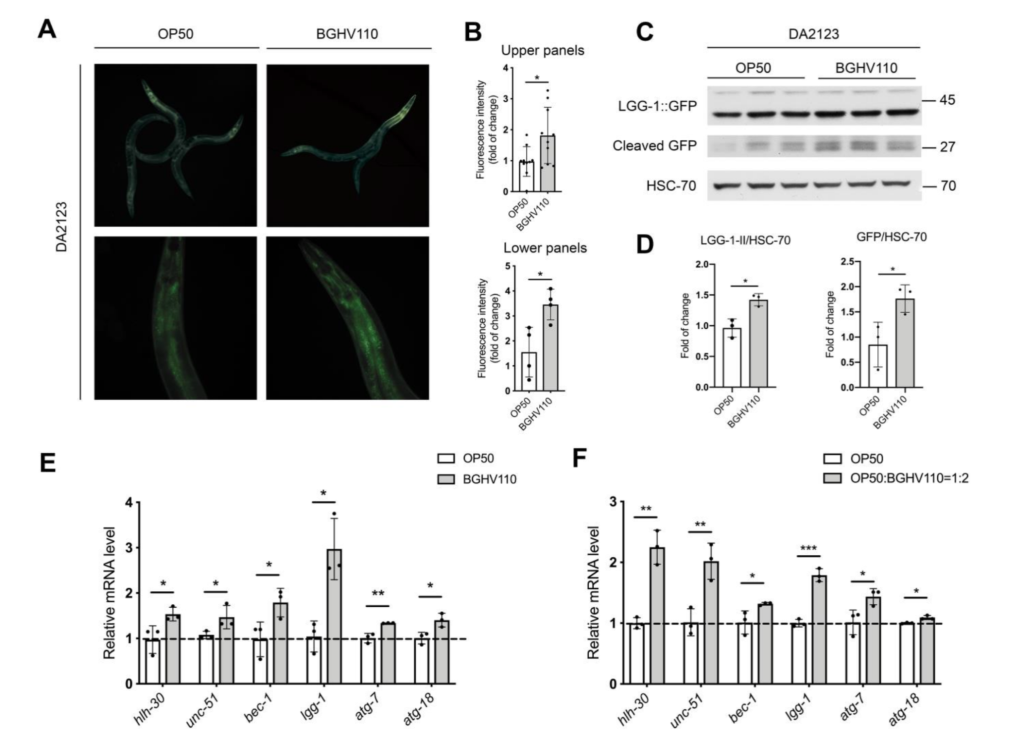

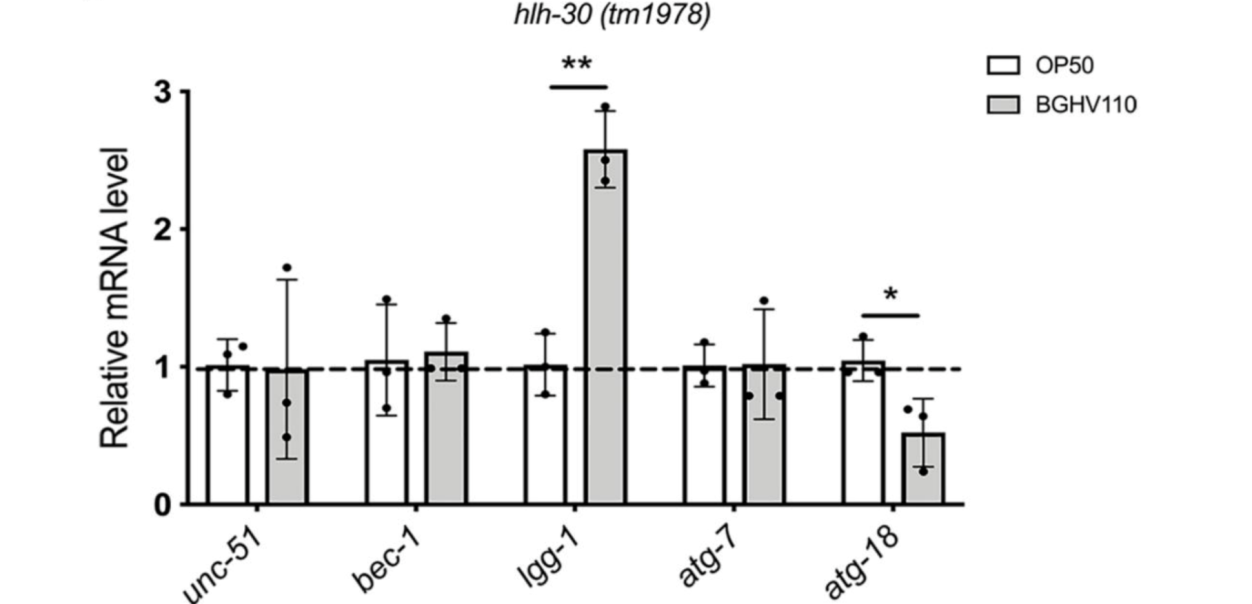

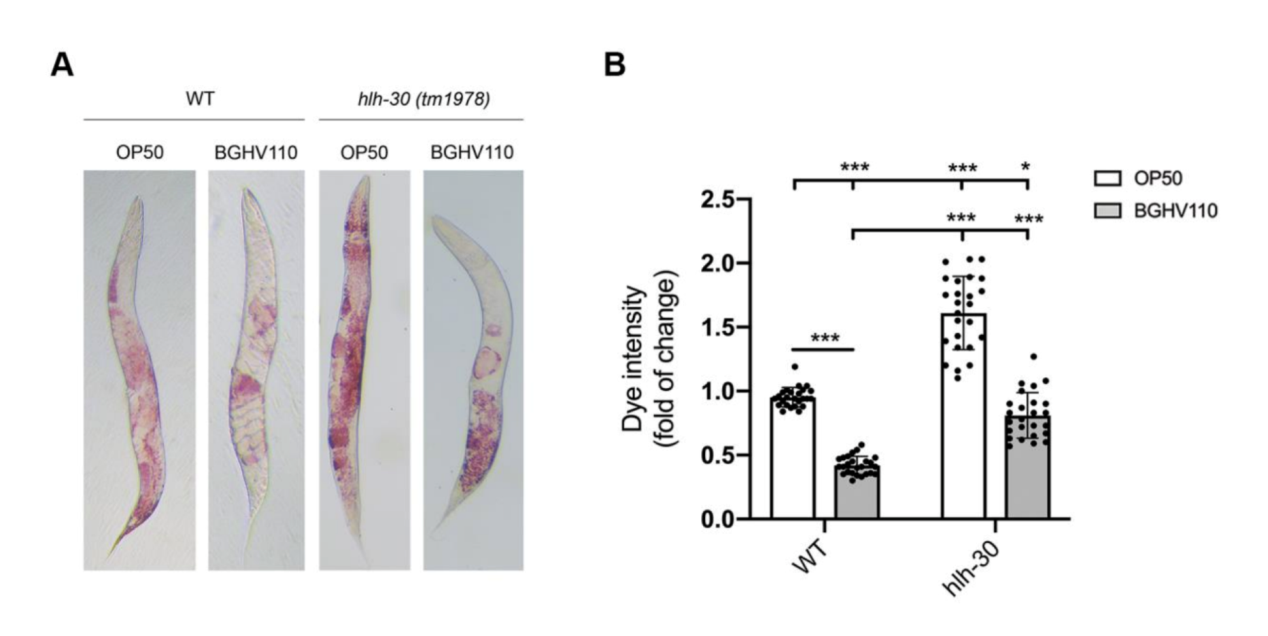

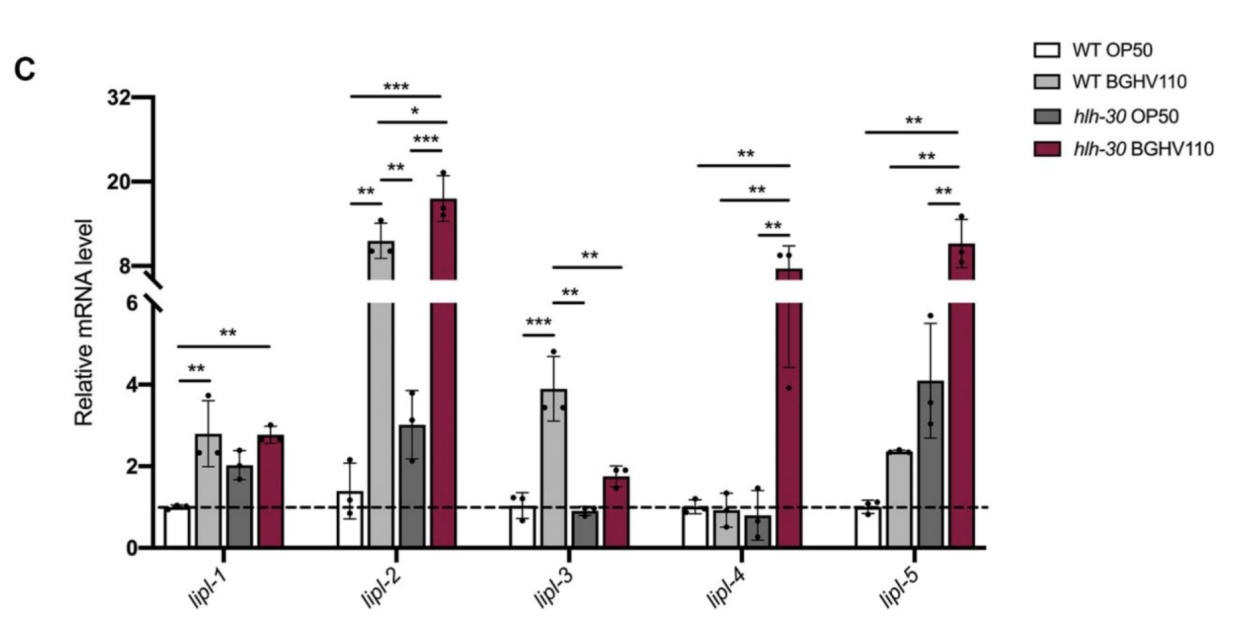

The upregulated autophagy observed above was mediated by the HLH-30 regulator. It was suspected that the HLH-30 regulator played an essential role in the whole mechanism and a hlh-30 defective mutant strain (tm1978) was introduced to test the hypothesis. The results obtained were in line with the speculation. The benefits observed in the wild-type worms upon feeding on BGHV110 were totally absent among the hlh-30 mutants feeding on the same postbiotics. Moreover, the physicalities of these worms remained on par with that of those feeding on OP50(Figure 3.). Getting deeper down to the molecular level, the researchers found that the genes involved in the autophagy process also hadn’t seen any sign of upregulation other than that of the lgg-1 gene(Figure 4.), and hence, it’s safe to conclude both that HLH-30 is required for autophagy to work properly, and that the lgg-1 gene alone is insufficient to trigger autophagy. One other physiological property that’s regulated by HLH-30 is fat storage and fat accumulation is also considered one of the hallmarks of aging. So, how’s the diet on BGHV110 having any impact on this front? The analysis on the trials comparing parallelly the WT worms and hlh-30 mutant worms on different diets revealed that feeding on BGHV110 has an effect of reducing fat accumulation on both the WT and the mutant worms, and even to a similar degree(2.2 fold decrease for the WT and 2 fold for the mutant, compared to the control(Figure 5.)). Now that’s confusing since we previously saw that feeding on BGHV110 had no positive impact on the longevity of the mutant worms. To further understand that, the researchers looked at the expression of several lipl genes, the ones that encode lipases. In the WT worms, an elevated transcript was found on the lipl-1, lipl-2, and lipl-3 genes, and the same elevation for lipl-2, lipl-4, and lipl-5 genes in the mutant worms(Figure 6.). It seems that HLH-30 regulates the transcript of lipl-1 and lipl-3 genes which will be activated during lipophagy, and the activation of lipl-4 and lipl-5 belongs to a lipophagy-independent pathway.

Figure 3. Conditions on aging and body-bending between mutant worms feeding on BGHV110 and OP50.

Figure 4. Transcript of autophagy-related genes for the mutant worms.

Figure 5. Analysis of fat accumulation.

Figure 6. Activation of lipase-encoding genes.

It’s no longer a surprising scene to see someone chucking down a handful of supplements these days. Now it’s time to widen that horizon. Gut health is essential for a person’s wellbeing, but we so far haven’t had much clue about their relation to autophagy, and eventually to the prospect of healthy aging. This paper shed some light to the ill-illuminated tunnel, and surely, there’d be more to come.

Reference:

Dinić M, Herholz M, Kačarević U, Radojević D, Novović K, Đokić J, Trifunović A, Golić N. Host-commensal interaction promotes health and lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans through the activation of HLH-30/TFEB-mediated autophagy. Aging (Albany NY). 2021 Mar 26;13(6):8040-8054.

doi: 10.18632/aging.202885. Epub 2021 Mar 26. PMID: 33770762; PMCID: PMC8034897.