The Histone Chaperone SPT2: A Key Regulator of Chromatin Structure in Metazoa

2026-01-07 16:33

Keywords

Histone chaperone SPT2, Chromatin structure regulation, H3-H4 binding, Chromatin accessibility

Contribution of SunyBiotech

SunyBiotech is very honored to provide strain construction services for this study.

Strains:

JRG30 spt-2(syb1268) IV,

JRG31 spt-2(syb1269) IV,

JRG48 spt-2(syb2412[M627A]) IV,

JRG44 spt-2(syb1735[mAID-gfp::spt-2(wt)]) IV,

JRG45 spt-2(syb2435[mAID-gfp::spt-2(M627A)) IV,

PHX4133 spt-2(syb2412,syb4133[A627M]) IV

Introduction

Histone chaperones are crucial players in the dynamic regulation of chromatin, which is fundamental for processes like gene expression, DNA repair, and replication. The histone chaperones SPT6, SPT5, ASF1 and the HIRA and FACT chaperone complexes have been implicated in promoting histone disassembly and recycling at active genes. Budding yeast Spt2 is a poorly understood histone chaperone implicated in histone H3-H4 recycling during transcription. The X-ray crystal structure of the histone binding domain (HBD) of human SPT2 bound to a H3-H4 tetramer has been reported. Replacing the HBD in yeast Spt2 with the human HBD suppresses cryptic transcription, similar to wild-type yeast Spt2, but mutating Met641 in the chimeric protein blocks this suppression. This shows that human SPT2 can regulate H3–H4 function, at least in yeast, but similar roles in human cells have not yet been described. Giulia Saredi et al. (Nat Struct Mol Biol., Mar 2024) explored the role of SPT2 in regulating chromatin in both the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) and human cells, shedding light on its impact on chromatin dynamics and its involvement in transgenerational gene silencing and stress responses.

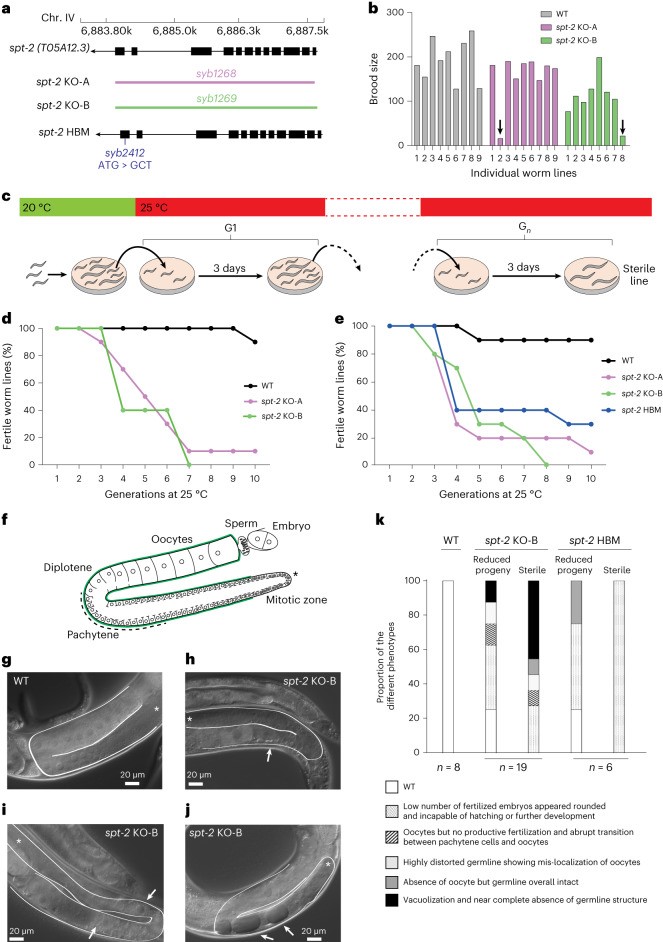

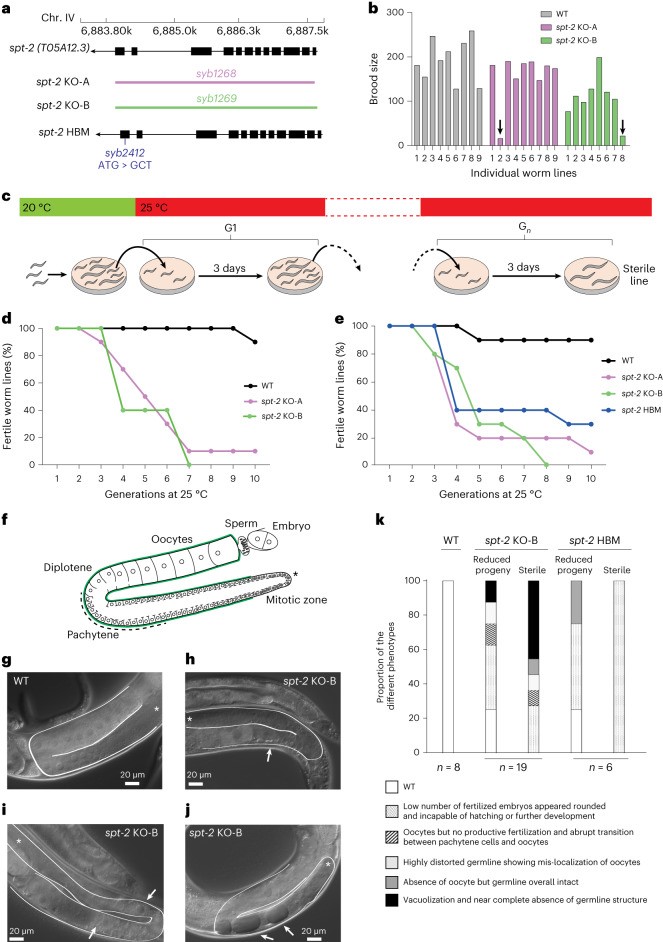

SPT2 in C. elegans Germline Development and Epigenetic Silencing

Previously, no C. elegans ortholog of SPT2 had been reported. Through iterative similarity search, the authors discovered an uncharacterized open reading frame, T05A12.3. After identification, it was confirmed to be an H3-H4 binding ortholog of SPT2, which the authors named CeSPT-2. Two independent spt-2 null C. elegans strains (spt-2KO-A and spt-2KO-B, Figure 1a), in which the spt-2 open reading frame was deleted, were generated to assess CeSPT-2 function. Both null strains were viable and produced brood sizes comparable to wild type at 20℃, but when cultured at 25℃ a subset of animals produced markedly fewer progeny after a single generation (Figure 1b). The frequency of sterile animals increased progressively over successive generations at 25℃, and after approximately 10 generations very few fertile worms remained (Figure 1c-e). A knock-in allele carrying the HBM substitution that weakens CeSPT-2 binding to H3-H4 (spt-2HBM, Figure 1a) also showed an increased incidence of sterility when grown at 25℃ for several generations, although less severely than the nulls (consistent with residual histone binding). Reversion of the A627 HBM substitution back to wild type (Met627) restored fertility, demonstrating that loss of CeSPT-2 histone binding causes the phenotype.

In WT nematode gonads, germ cells transit in an orderly manner from the mitotic stem cell state to the various stages of meiotic prophase (pachytene and diplotene) and eventually become fully mature oocytes (Figure 1f-g). In contrast, the microscopic analysis of the spt-2 mutant germline revealed multiple abnormalities at 25℃: oocytes but no productive fertilization, abrupt transition between pachytene cells and oocytes (Figure 1h), abnormal oocyte localization (Figure 1i), and vacuolization (Figure 1j). Taken together, these data show that the onset of sterility in spt-2-defective worms is associated with pleiotropic defects in germline development (Figure 1k).

Figure 1. Loss of CeSPT-2 histone binding causes germline defects and sterility.

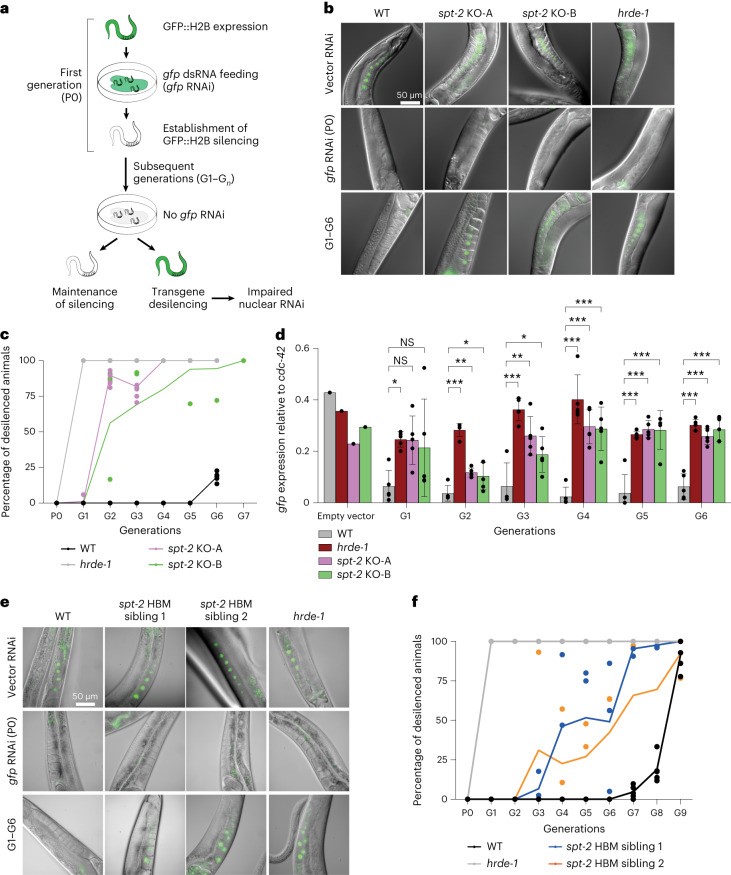

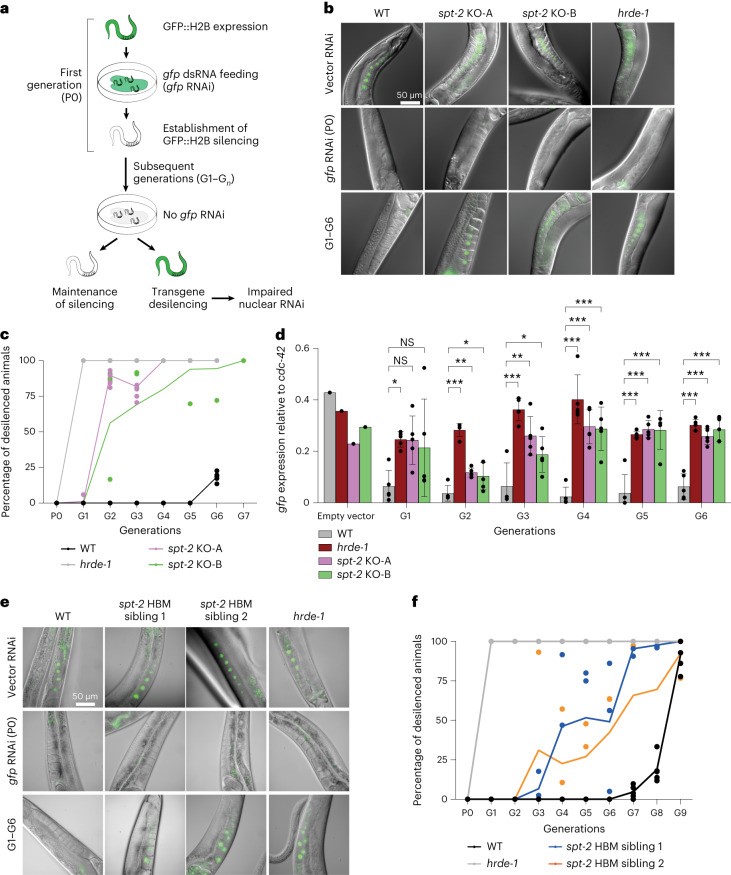

SPT2 and Gene Silencing

CeSPT-2 is essential for the transgenerational inheritance of gene silencing mediated by the nuclear RNA interference (RNAi) pathway in C. elegans. The progressive sterility observed in spt-2 mutants at elevated temperature resembles phenotypes associated with defects in nuclear RNAi. The gfp::h2b single-copy transgene that is constitutively expressed in the worm germline can be silenced by feeding worms with bacteria expressing double-stranded gfp RNA (gfp RNAi, Figure 2a). Authors showed that initial RNAi-induced silencing occurs normally in both spt-2 null and hrde-1 mutant worms (Figure 2b-c). However, whereas silencing persisted for multiple generations in wild-type animals, it was lost in the first generation (G1) in hrde-1 mutants and in the second generation (G2) in spt-2 null mutants after removal of the RNAi trigger, as measured by GFP fluorescence (Figure 3b-c) and mRNA abundance (Figure 3d). Also, the spt-2HBM strain showed transgene desilencing albeit slightly later than in the null strains (Figure 2e-f). These findings demonstrate that CeSPT-2 is required for the maintenance and transgenerational transmission of epigenetic gene silencing.

Figure 2. CeSPT-2 histone binding is required for transgenerational gene silencing.

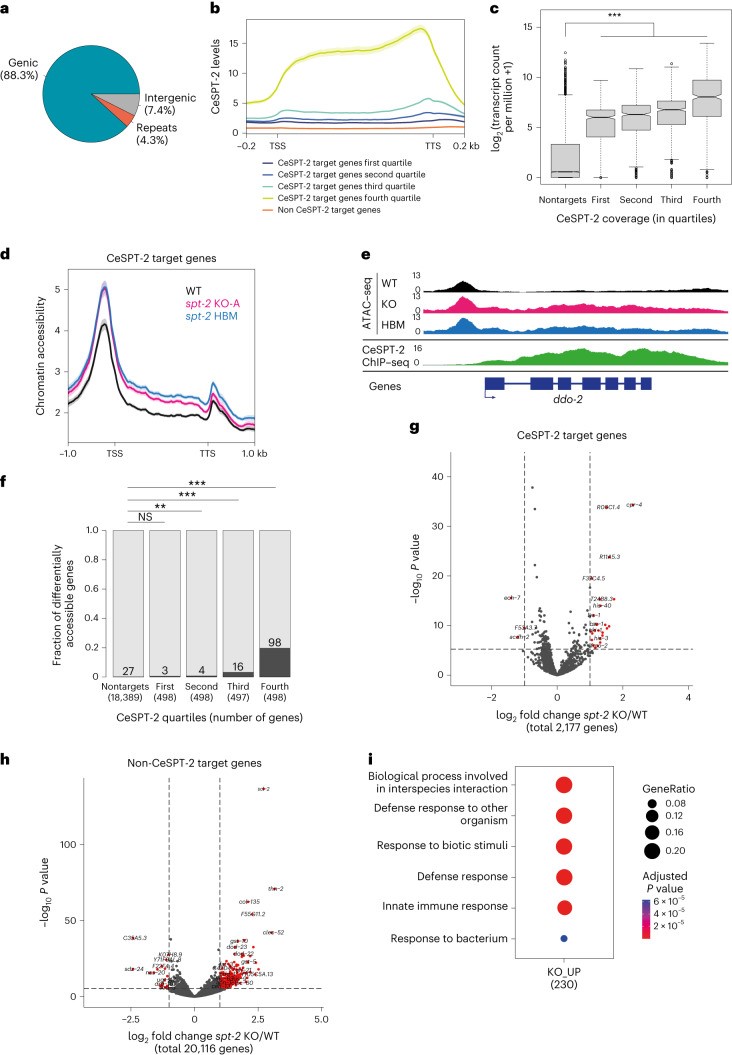

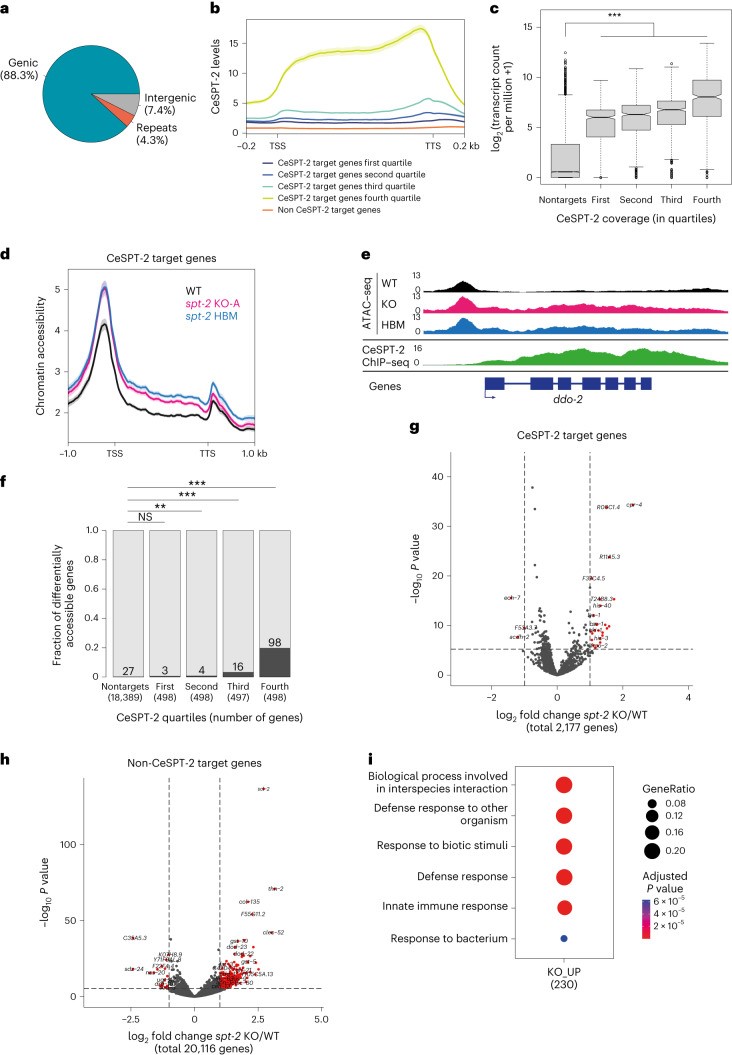

CeSPT-2 controls chromatin accessibility of its target genes

Genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing revealed that around 88% of the regions enriched for CeSPT-2 binding lie within genic regions (5,299/6,003 sites), with the remaining sites found in intergenic (~7%, 258 sites) or repetitive (~4%, 446 sites) sequences (Figure 3a). GFP::CeSPT-2 enrichment was observed over the entire length of what the authors hereby call ‘CeSPT-2 target genes’, with an apparent enrichment for the 3′ end of the gene (Figure 3b). CeSPT-2 binding positively correlates with transcriptional output, and the majority of the most highly expressed genes in the genome are CeSPT-2 targets (Figure 3c). Assays for chromatin accessibility showed that in both null and HBM spt-2 mutants, the chromatin accessibility increased across the entire length of the gene body of a subset of CeSPT-2 bound genes (KO: 121/1,991, HBM: 105/1,991, overlap: 88; Figure 3d-f). These results indicate that histone binding activity is needed for chromatin accessibility regulation.

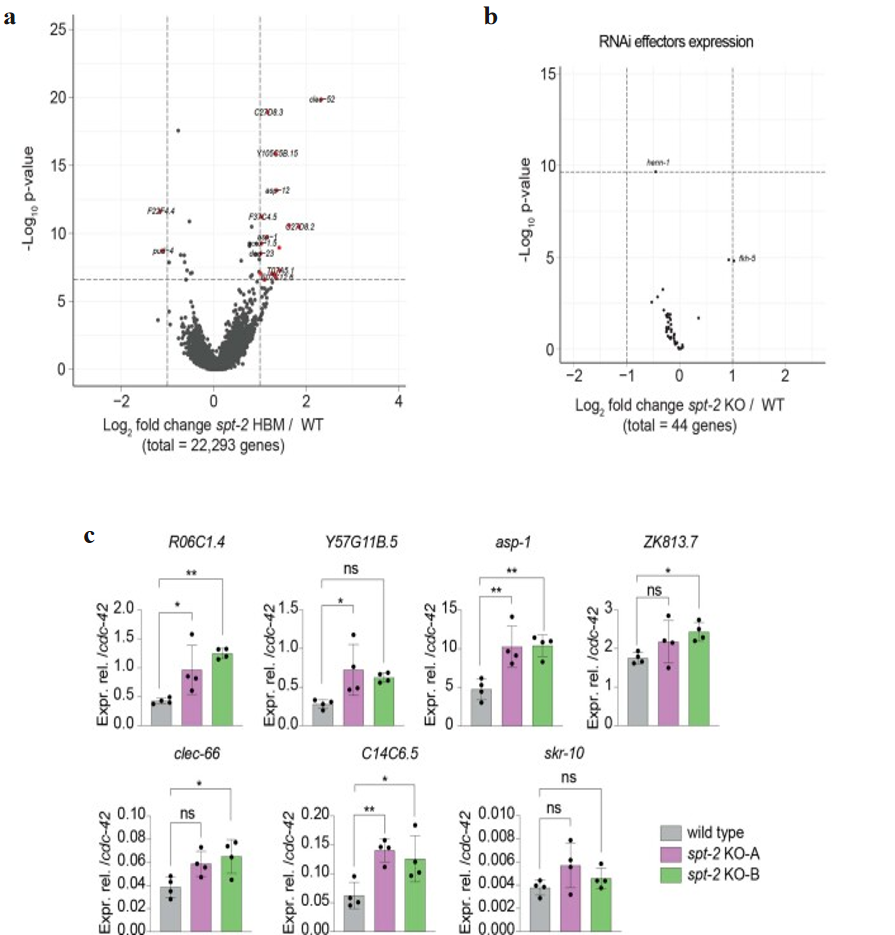

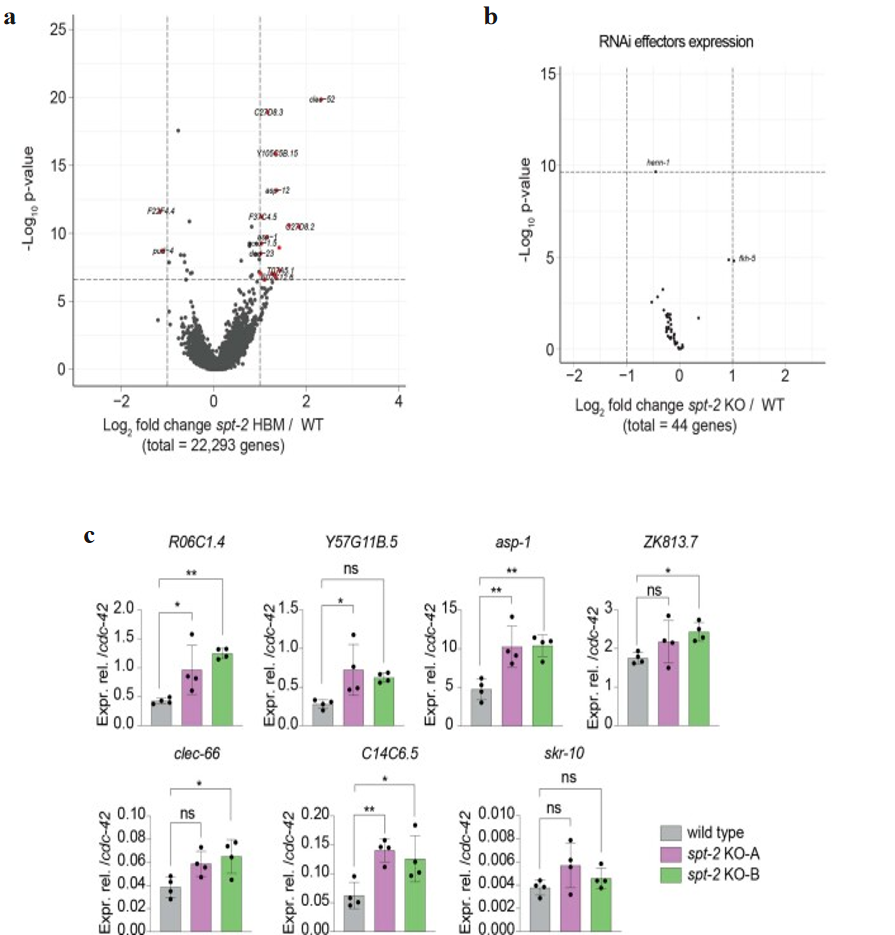

Transcriptome analysis further revealed that complete loss of spt-2 (spt-2KO-A) causes widespread gene upregulation, whereas the histone-binding mutant (spt-2HBM) shows minimal transcriptional changes (Figure 3g-h and Extended Data Figure 3a,c). Of note, the expression profiles of genes involved in the RNAi pathway is largely unaffected (Extended Data Figure 3b). Only a small fraction of upregulated genes in the null mutant are direct CeSPT-2 targets, indicating that most expression changes arise indirectly (Figure 3g-h). Notably, the induced genes are enriched for defense and stress-response pathways, consistent with a global stress state (Figure 3i). Expression of core RNAi machinery genes remains largely unchanged, arguing against indirect effects on RNAi through altered effector levels. Together, these data support a model in which CeSPT-2 binds chromatin at highly transcribed genes to regulate accessibility and maintain epigenetic stability, while its loss triggers secondary stress responses and compromises transgenerational gene silencing.

Figure 3. CeSPT-2 histone binding controls chromatin accessibility.

Extended Data Figure 3. Volcano plot of gene expression levels in spt-2 HBM versus wild type worms and mRNA-seq analysis in spt-2 mutant worms.

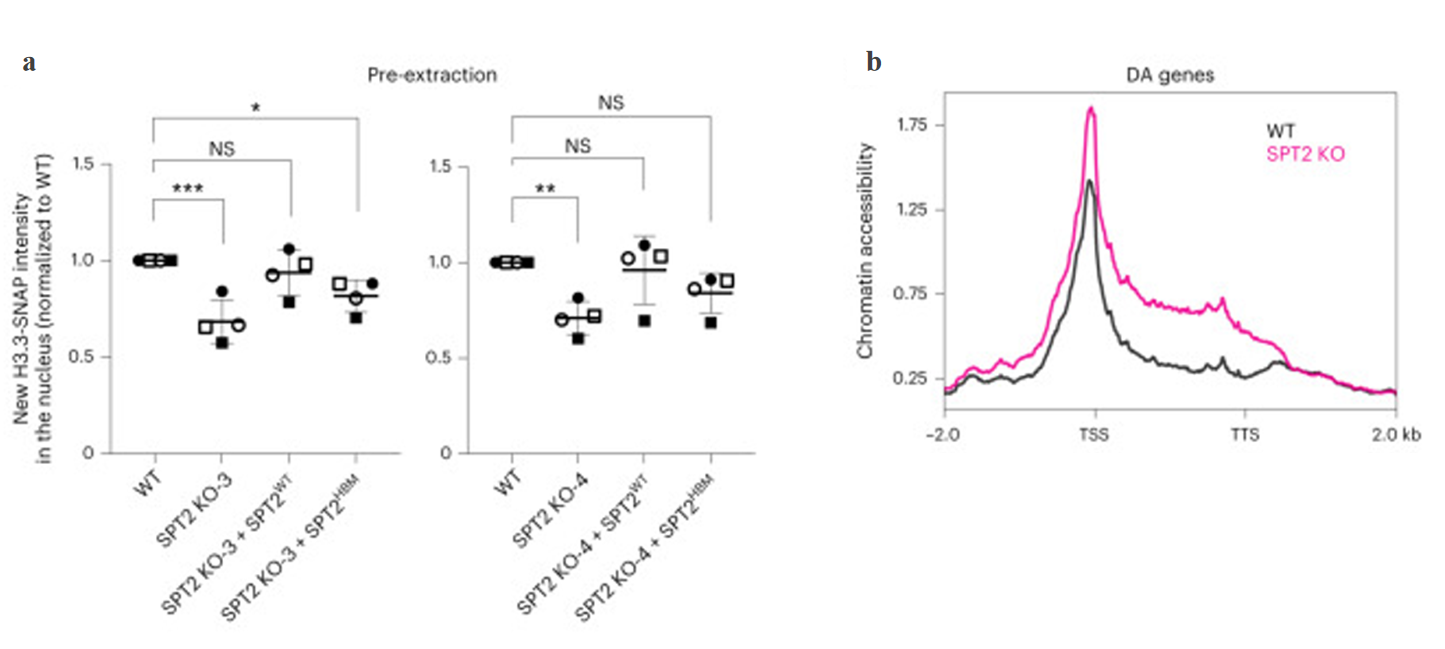

Human Cells and Histone H3.3 Regulation

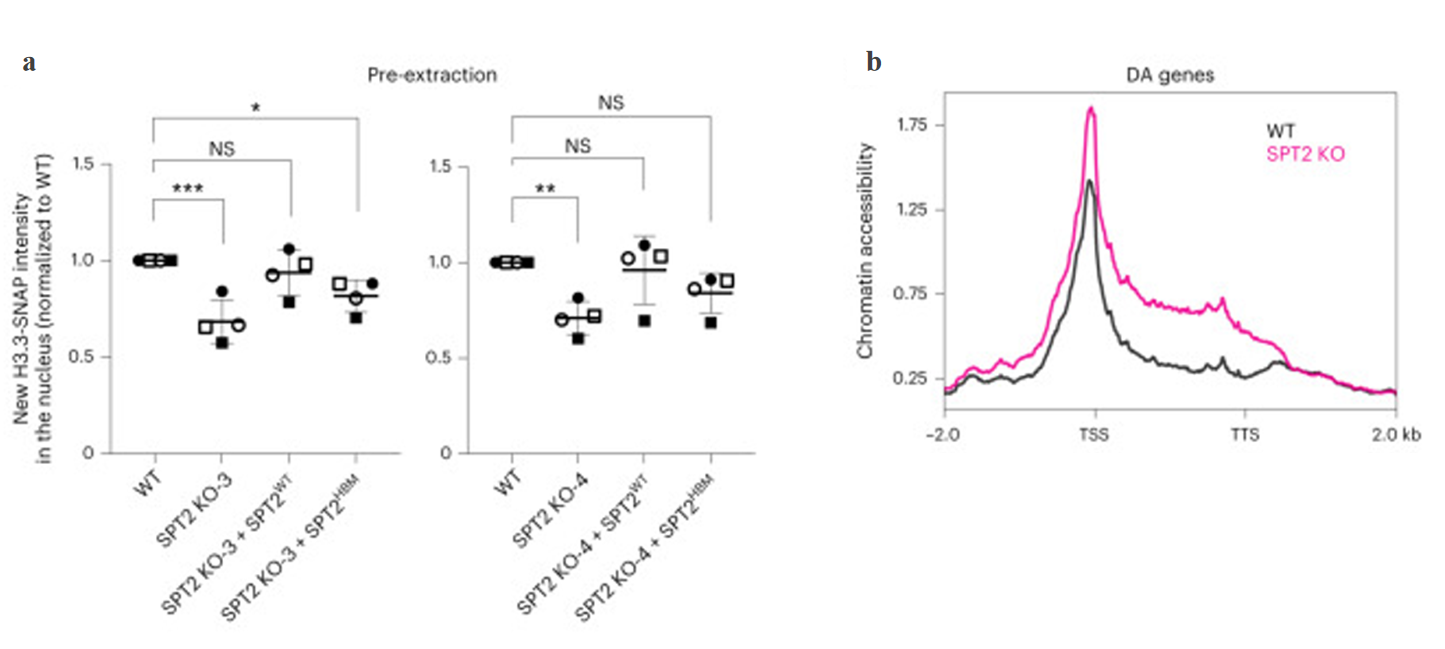

The role of SPT2 is not limited to worms. In human cells, SPT2 has been shown to regulate the incorporation of histone variant H3.3 into chromatin. SPT2 mutants displayed reduced levels of chromatin-bound H3.3, and this reduction was associated with increased chromatin accessibility at certain genes (Figure 4). This highlights SPT2's role in preserving chromatin structure in human cells, especially at actively transcribed genes. The study also explored the interplay between SPT2 and the HIRA histone chaperone, another key player in chromatin maintenance. In worms, the loss of both SPT2 and HIRA resulted in severe developmental defects, including sterility and morphological abnormalities. This suggests that SPT2 and HIRA may function cooperatively to regulate chromatin integrity in response to developmental and environmental cues.

Figure 4. SPT2 binding to H3–H4 regulates the levels of soluble and chromatin-bound H3.3 in human cells.

Conclusion

Overall, this research highlights the pivotal role of SPT2 in regulating chromatin structure and function across species. In C. elegans, SPT2 is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the germline, supporting transgenerational gene silencing, and preventing stress-induced chromatin decondensation. In human cells, SPT2 regulates histone incorporation and chromatin accessibility, underlining its importance in preserving chromatin architecture during transcription and other cellular processes. The findings also emphasize the complex interactions between histone chaperones, which collectively ensure the stability and function of the genome.

Reference

Saredi G, Carelli FN, Rolland SGM, et al. The histone chaperone SPT2 regulates chromatin structure and function in Metazoa. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2024 Mar;31(3):523-535.

doi: 10.1038/s41594-023-01204-3.